Planning policy guidance on change of use has been accused of being “badly blurred” by the High Court in deciding whether a personal trainer required planning permission for change of use for his home gym. Before asking for new guidance, it is worth applying a dollop of common sense.

The facts

The appellant – a personal trainer – converted a shed/building in his garden to a gym so that he could work from home. Bromley LBC (twice) rejected his application for a certificate of lawful use. Mr Sage appealed both refusals – with both appeals being dismissed. His legal challenge was rejected.

The Judge agreed with the inspector that the business use was neither incidental nor trivial to the enjoyment of the dwelling house. Consequently, there had been an overall change in the property’s use and character and planning permission was required.

So… how did we get here?

The Judge held that “a business use in a dwellinghouse may well be secondary to the primary residential use of the dwellinghouse; but may still create a material change of use, be for a non-incidental purpose“. Likewise, “a material change of use can be made without any adverse environmental impact at all” and that “[t]he crucial test is whether there has been a change in the character of the use.”

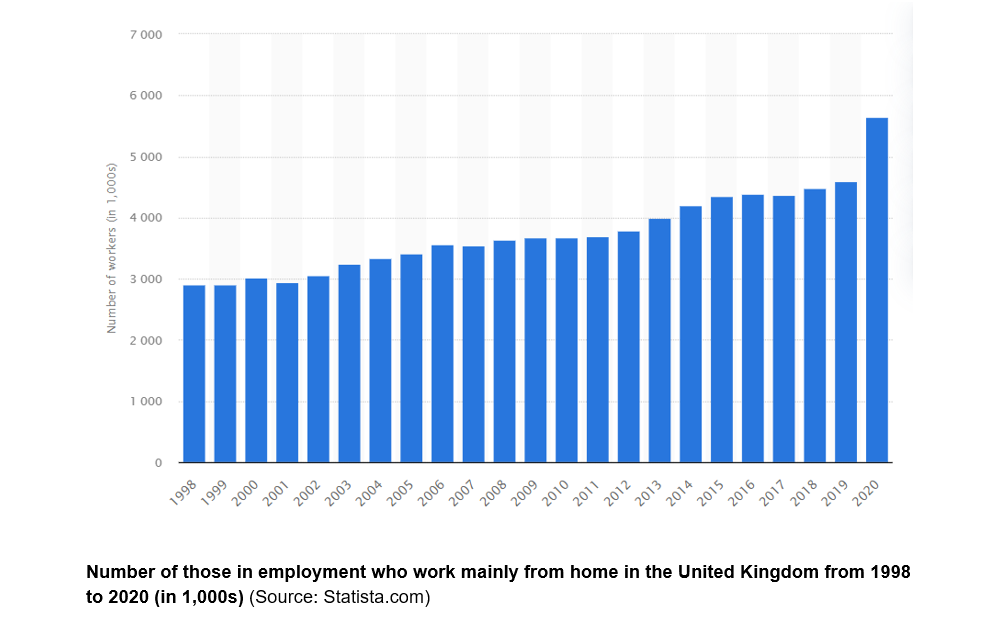

Notably, “I accept that what is normal or reasonably incidental now may have shifted with changes in work habits as a result of Covid…an important distinction would have to be drawn between working from home, where work-related visitors were few and far between, and working from home with took the form of routine and frequent work-related visitors, notably customers.”

See the graph below showing interesting, but incremental, changes.

So what?

Change of use debates will continue to rely on planning judgement. The Judgment confirms that the PPG needs a tweak, but we should be wary of seeking even more guidance.

The rules after all are pretty clear:

- Dominance is not the whole test – secondary uses should only be treated as ancillary where they are ‘ordinarily incidental’ to the main use. That is a restrictive approach (Harrods) and should not be confused with simply being secondary. The more dominant a use, the less likely to be incidental (but the key judgement is about what is a normal set of uses). The test is ultimately whether a use is ‘generally associated with what goes on’ in the main use.

- Change of character is the issue – amenity effects may be indicators, but do not dictate this.

- Common sense is key – the Courts have told us that neither keeping 44 dogs nor running a commercial gym are part and parcel of an ordinary residential use in a single planning unit, nor for that matter is landing a helicopter on top of a shop.

We should not be too surprised at these kinds of cases or spend time hunting for magic legal bullets and more detailed guidance.

The Judgment confirms that the “true emphasis” legally is on the character of the use, the objective component in what is incidental, the scale and nature of what is incidental, and the indirect relevance of environmental impacts.

Planners are better qualified than lawyers to address those issues. In doing so, practitioners should bear in mind the scale of shifts in residential norms are sometimes overstated.

With thanks to Amy Carter for assistance with this blog.